He was as elusive and mythological as the Abominable Snowman, as mysterious and as feared as Loch Ness and Bigfoot. But he was somewhere among us in Central Maine. For both the dwellings of his victims and his own abode were all just a 12-mile straight line distance from Downtown Waterville. They were coincidentally only about seven miles from the Belgrade Lakes cabin where Stella Crater said goodbye to her husband, Judge Joseph Force Crater, three days before he became in August of 1930 the “missing-ist” person of the 20th century. They were also a mere three miles from the north shore of Great Pond, the model for Ernest Thompson’s acclaimed novel, “On Golden Pond.”

He wound up committing over a thousand burglaries in a 27-year period, one of the largest strings of separate break-ins tied to a single criminal in American history.

This is of course none other than one of the most publicly known yet at the same time private persons in Maine, Christopher Knight.

His capture four years ago April 4 – just 11 days before the Boston Marathon Bombing – gave rise to a sigh of relief that his escapades would now end. It also provided some measure of assurance that he was neither a bomber, a terrorist, nor a murderer, something his victims had no way of knowing until his capture. He was instead a 47-year old with no prior criminal record. He was a native Mainer from Albion – the same home town as Mickey Marden, who just the year before Knight was born, founded one of the state’s best known chains of discount department stores.

Despite Knight’s shocking portfolio of thefts, Knight was nevertheless an extraordinary being who achieved one of the most challenging and enduring outdoor personal survival narratives ever. It is doubtful if any known person in recorded history has ever been as secluded as Knight, having exchanged only the single syllable “hi” to one other individual in over a quarter century. And, during the five coldest months of each of these 27 years – when due to the prospect of leaving footprints in the snow he largely refrained from his nefarious activities – he kept himself alive in an outdoor tent without so much as striking a match, not to mention lighting a fire.

In this entire time he also claims that:

Never got sick.

Never got bored.

Never got lonely.

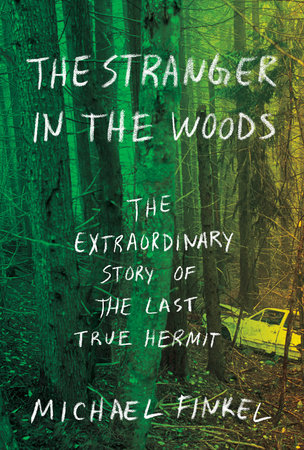

His story is now told in The Stranger in the Woods, the Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit, by Michael Finkel that was over three years in the making, released just earlier this month. It is one of the more spellbinding repertoires of philosophy, psychology, sociology, medicine and crime ever assembled between the covers of a single book.

Despite the ambitious array of subjects it’s a concise 200-page smoothly blended read that moves quickly.

This is due in part to Finkel’s background as an investigative journalist, his articles appearing in the likes of National Geographic, GQ, Rolling Stone, and the New York Times Magazine. (It was from the latter where he sustained his own ethical blemish in 2002 when it discharged him for creating a composite character in a story he did on the African slave trade. His career has long since been in remission, especially with the publication of True Story: Murder, Memoir, Mea Culpa in 2005, on an Oregon murder suspect who took Finkel’s name and part of his identity while a fugitive.).

Where Finkel’s investigative skill is most at the forefront in the Stranger in the Woods is his ability to develop a connection with his subject. In this, he astoundingly stands out. For what District Attorney Maeghan Maloney dubbed “the most famous person in Maine” had in the first two months after his arrest rebuffed hundreds of TV, newspaper, magazine and internet reporters seeking to talk to him. Though cooperating with law enforcement, Knight had no word to say to any member of the Fourth Estate.

No word, that is, until Finkel sent a sensitively composed handwritten letter to him in June 2013, two months after his arrest. Besides expressing compassion for Finkel’s plight, it enclosed copies of some of his recent magazine articles including a National Geographic story Finkel had done on a small Tanzanian tribe that lived in primitive conditions in the bush.

Knight’s brief handwritten reply just a week later inaugurated a series of five letters and eventually nine interviews that have become the foremost means by which a window has been opened to Knight’s world. Though some of what Knight told Finkel was revealed in a 2014 GQ article, Finkel’s book is more expansive. Moreover, it includes a series of mini-essays on the historic context of his phenomenon, how medical and psychological professionals diagnosed Knight, and how Finkel’s heightened ingenuity allowed him to survive the cold winter months. The book also helps answer the question of how Knight was able to evade capture over so many years despite placement of modern technical detection devices designed to snare him. (Only a rarely used Homeland Security sensor system was finally able to accomplish this. )

As Finkel, whose own resume includes reporting from over 50 countries throughout the world, observed in an interview with me earlier this month, “There are very few times in my life when I have been so daunted by one person’s brainpower. This guy is hyper smart. He can remember every page of every book he ever read and then he could quote Shakespeare but he also knows thermodynamics … he knew how to repair an engine and electrical stuff and he could build things … almost too smart for this world.”

Knight’s perceived brilliance, according to some scientific research Finkel relies on in the book, is something that was likely enhanced by Knight’s time alone in a natural environment. According to this hypothesis, then, Knight was a smarter person after he had finished his hermitage than when he had embarked on it.

Finkel stands out as having made a more significant effort than most writers this columnist has encountered to ensure accuracy, something crucial when – as here – the protagonist has provided such limited access. “I could have bought a new car with the money I spent on professional fact checkers,” he told me.

Law enforcement officers and Knight’s lawyer were among the others Finkel tasked with the job of going over pertinent portions of the manuscript to make sure its mind boggling story was not accidentally detoured into cavities of fiction.

The dozens of victims of the more than 1,000 burglaries Knight committed probably wish that it had all in fact been merely imaginary. There is nothing about Finkel’s book that should push to one side the anguish many of them felt about the insecurity Knight inflicted on them. Some children in the area having nightmares about his recurring exploits were among the examples the book provides. It’s a fear that both Knight and Finkel readily acknowledge as being justified. That is of course the tragedy that will forever haunt Knight’s legacy. It will and should keep him from being unduly glorified.

Knight was, however, immediately forthcoming to the game warden and state police officer who took him into custody what techniques and tools he used in performing what had been up until then one of the nation’s most enduring run of burglaries. Home and camp owners might well be better on guard against such predations in the future. Theirs are now less vulnerable not only as the outcome of his capture but also as the result of his revelations.

Though Knight will not likely ever be redeemed, he has achieved some measure of dispensation. After serving a seven-month jail sentence, he successfully completed three years of probation. Staying out of trouble has certainly been one way of satisfying his craving to resume an anonymous existence.

He is now believed to be living with his octogenarian mother in the same Albion home where he grew up, working out of her house in connection with his brother’s sheet metal business and occasionally putting in time doing chores for the local historical society.

A further form of penance and a feature of Knight’s rehabilitation could be his imparting to civil defense and military authorities additional clues to his techniques of outdoor survival during the coldest months of over two dozen Maine winters, times when he largely refrained from committing burglaries. This has in some measure already been accomplished by the publication of Finkel’s book and answers he gave during his interrogation by arresting officers. One can’t help but think that Knight’s reticence on this and many other subjects has not yet been completely overcome.

In any book that puts its arm around so broad a subject in such a short space of pages it’s inevitable that a lot of detail has wound up on the cutting room floor. This is also true for Finkel, who spent thousands of hours spending time with nearly all the 40 families owning homes stricken by Knight others in the town where Knight grew up, speaking with doctors and psychiatrists, state police and game wardens, not to mention reading over 100 books about hermits and of course exchanging letters with and speaking to Knight himself.

In writing a book, “I put down every single thing I can think of about the subject and I make what I call my block of granite,” as Finkel explained to this columnist.

“From that block of granite I chisel out a book. My original block of granite for this book was 1,500 pages,” Finkel concluded.

An aspiration many may have once reading the book is that more of what Finkel left out could be offered in a more unabridged sequel. One can easily predict that popular demand might well encourage him to do this.

I hope he does.

Paul Mills is a Farmington attorney well known for his analyses and historical understanding of public affairs in Maine. He can be reached by e-mail at pmills@myfairpoint.net

If you live in Maine this is a must read book !!

Nice article, Paul. I enjoy your writing.

Story of the North Pond hermit and Finkel’s book was also broadcast on NPR

and was every bit as fascinating as Paul Mills describes…”one of the more spellbinding repertoires of philosophy, psychology, sociology, medicine and crime ever assembled between the covers of a single book.”

It seems to me, with the articles that I have read, the news story on NPR and various other news outlets, that this man is being glorified for the things he has done. I understand that living in the woods in seclusion is a “big deal”, but what is being swept under the rug of all that is the fact that this man stole many items from many people over a long period of time. He invaded their houses, garages and camps taking things that didn’t belong to him and creating a sense of unease and mistrust in people all around him. If you’ve never had your house broken into, or anything stolen from you, let me assure you that the fact that he is “harmless” and just wanted to “be alone” is small comfort. He has not expressed any real remorse in the things that he has done, nor has he had to make any real amends for any of it. The fact that the items he took are not considered overly valuable as a whole is not the point. What he truly took from those around him cannot be measured in dollars and cents. He took away peoples sense of security and comfort in their own homes, and the trust in their fellow men. Those are things that are irreplaceable. I, for one, am not planning on glorifying him by spending one dime or one more minute of my time reading tales of his “adventures”.

Where can one purchase this book? Thank you!

He is NO hero — he is a thief!

Too much glory going to a crook !!! Paul’s writing is exceptional in many ways, however I would not ever want to support a book that would in any way “glorify” thievery and burglary…..Just ask those who were robbed !!!!! I’m sure they have a similar response……

Hope this guy Knight is not getting any royalties from this book, he doesn`t deserve anything. Furthermore, he should be paying back to everyone he stole from .

i have not read this book, but i did read the lengthy excerpt that was published in the guardian, and there was no indication that the subject was being glorified or that his crimes were being excused. far less interesting works have been written about far more reprehensible people.

Finkel does not “glorify” Knight nor in any way justify his thefts. For that matter, neither does Knight in telling about them, often expressing remorse for what he did. Curious that people criticize so hotly a book they’ve not read.

Thanks, Paul, for the excellent review. It is, indeed, a remarkable book and a serious study in human nature.

Yes Larry Bisbee! Exactly!

Josie,

The way publishing works is that the author is paid an advance for her or his work. The author then receives royalties from the publisher once the book has met sales enough to pay for the advance.

The subject of the book, in this case Mr. Knight, does not receive royalties.

If you buy the book, which I plan to do, your money does not go toward Mr. Knight but rather to Mr. Finkel’s totals so that someday he can receive royalties.