By Paul Mills

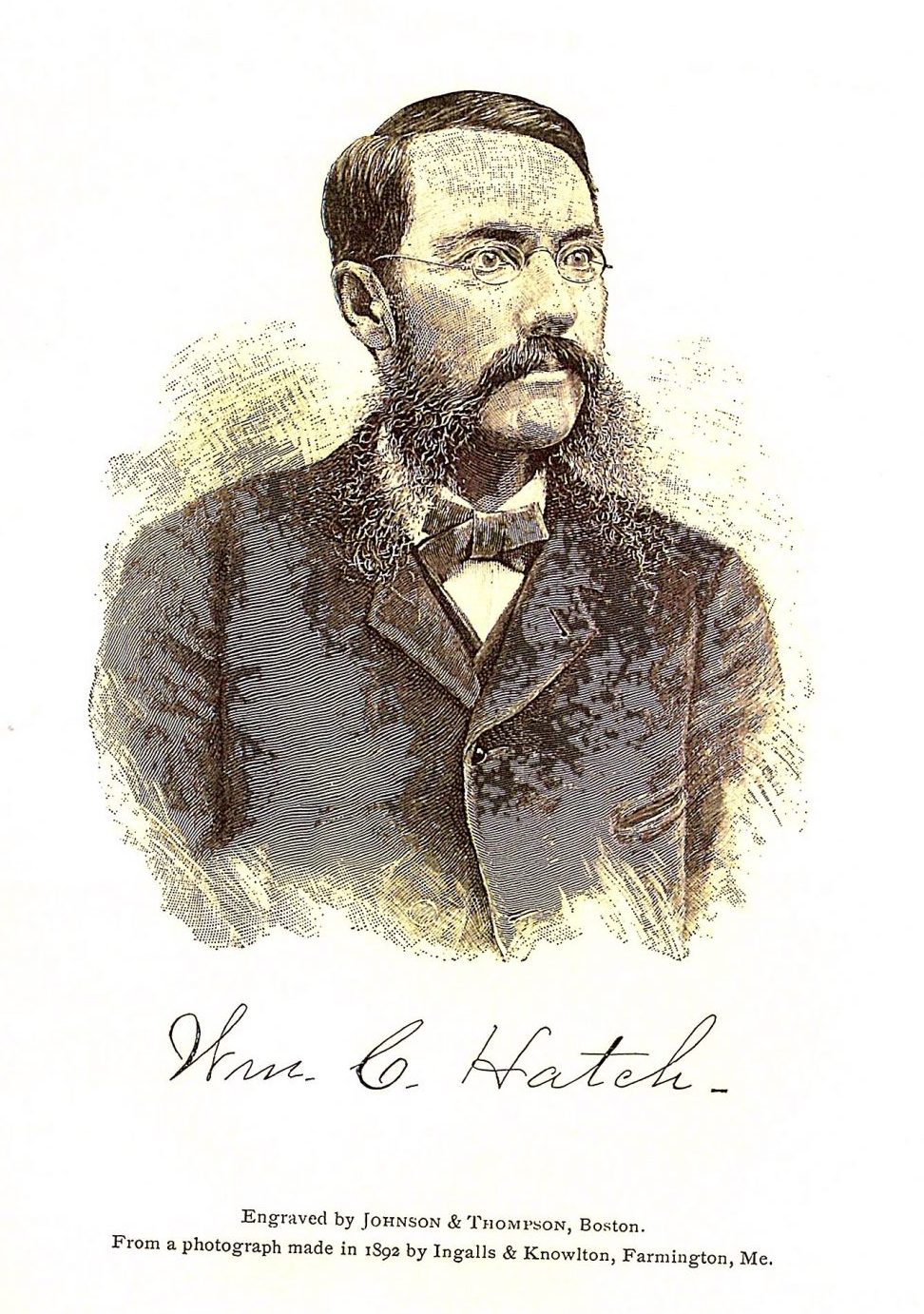

Like a lot civic minded professionals, Dr. William Hatch liked to travel. Befitting one who had been president of the Maine Eclectic Medical Association and who was then the secretary of the New England chapter, the New Sharon based physician was often drawn to the drama of urban life. An accomplished historian he was the author of what remains today one of the best written and thorough portrayals of any community in the state, his 862-page 1893 History of Industry, Maine, a book much more expansive than the population – then just 545 – of the community might suggest.

In any event, in the late spring of 1902 Hatch went to a meeting of the National Eclectic Society in Providence, Rhode Island. After the conference Hatch traveled on an excursion boat from Narragansett Bay and down Long Island Sound to Manhattan. Accounts differ as to just what happened when he got there. In an interview Hatch gave to Maine Board of Health Secretary Doctor A.G. Young, a young man with an eruption Hatch believed to be smallpox brushed up against him while Hatch was on one of the city’s gangways.

Another account appears in a 1959 term paper for Farmington State (now UMF) by long time New Sharon resident Blandine Buzzell. According to Buzzell Hatch while in New York visited a “pest house,“ a repository for housing patients with contagious diseases This is a place where the 51-year old Hatch did not consider himself personally vulnerable, though according to Dr. Young he refused to believe in the validity of vaccination.

A few days later, upon returning to his home at the center of New Sharon – in a location in its village center that was next to a building devoted to manufacturing woolen coats – later a renown tennis racquet factory – Hatch exhibited skin eruptions that were diagnosed as smallpox.

Fear soon gripped the entire town, then with a population of 1,000 persons. Though Dr. Hatch moved to live, and 19 days after contracting the disease, die, alone at cabin in a more remote section of town to which he was quarantined, fear of the spread of smallpox was such that New Sharon village became a ghost town, with no one either coming from or going to.

Fortunately, even though others including the doctor’s wife and 22-year old son exhibited smallpox, symptoms no other fatalities ensued.

Neither New Sharon nor Maine was as fortunate a few years later, however. This was of course the flu epidemic of 1918-19, which still stands – though obviously may perhaps be soon overtaken – as the most serious pandemic of modern civilization, infecting some 100-million world-wide, including some 47,000 in Maine with about 5,000 fatalities in the state.

The impact in Maine and its response then to the epidemic was similar but by no means identical to those we are witnessing in the state today. For one thing, rural areas then were more heavily infected. Aroostook County led the list. (Among those afflicted there and barely surviving the epidemic’s assault was this author’s maternal grandfather, 36-year old Ashland potato farmer and town clerk Laurence Coffin.) Piscataquis and Knox counties also reported higher death rates than the more urban Portland region. This is attributed in part to the greater scarcity of modern medical facilities.

In addition, the epidemic struck its fatal blow more among vigorous middle-aged or young adults than the elderly and infirm. Half of those who died were between the ages of 20 and 40. One of the first of those to succumb, for example, was the 36-year old secretary of the state senate, Capt. William Lawry. He died after a visit to the army’s Camp Devens in Massachusetts.

Farmington’s 43-year old postmaster, Joseph Linscott was another fatality. His experience illustrated a characteristic of the pandemic that was quite typical, namely, the short, often only three or four day interval between the onset of symptoms and death of the victim.

This author’s father, then 7 years old, once recalled that the young mothers of two of his Farmington friends also died suddenly. As a consequence his friends moved elsewhere to be brought up by relatives outside the area.

Just as with the situation today, many schools, state courts, and other public places were closed. In 1918 this was in the four week time frame from the end of September through end of October. Both the Topsham and Androscoggin Fairs were among those cancelled. The impact varied a bit more between communities than today, however. This was due to the fact that there was no state-wide or for that matter even national authority to enforce closures. Instead, each municipality was given the task of implementing its own mandates. Lewiston, for example, kept its schools open partly over a concern about child care. Some church services there were allowed to be conducted outdoors.

By Nov. 11, the time victory was declared in World War I, the epidemic had subsided and normal schedules resumed, for awhile at any rate. The epidemic flared up again in February 1919, however, and as before some public meetings were called off. By spring the “all clear” signal went out and, at least in the form that it had appeared just over a century ago, this flu was not to return.

Were Dr. Hatch to return to his New Sharon neighborhood he would find that the site of his home was now traversed by several thousand vehicles a day, traveling on a section of U.S. Route 2 put in its place in 1957. He would find that the factory building next door was still standing but now used as a fabric shop. Just across the street from his home site he would find a grocery, hardware-farm supply business, operated by one of the pillars of the community, Larry Donald, a former first selectman. The talking sign in front proclaims, “We will survive. Help us help you. Stay home. Call in,” followed by the store’s phone number.

Gifted historian and physician that he was I regret that Dr. Hatch could not pen his own observations on not only what has become of his neighborhood but both the 1918 and present day pandemics.

I am sure he would have a lot to say.

Paul Mills is a Farmington attorney well known for his analyses and historical understanding of public affairs in Maine; he can be reached by e-mail pmills@myfairpoint.net.

Paul,

I am in shock. Your reporting brings home how vigilant we must be to try to survive this latest pandemic!!

You provide the overview as well as detailing our local area in another time.

Let’s hope we can reduce the spread and stay home. Thank you. Be careful!

If only we didnt have to live so much life to understand the true value of history and what it tells us.