By Paul Mills

The parade of snow storms that has recently made its march through Maine has given rise to a number of disruptions to daily life. Among the facilities that are less likely to curtail their services besides our hospitals, snow removal, police and fire departments, is our post office.

Of course even the postal system delays delivery and closes its windows earlier than normal when struck by severe weather, something that would happen even if Cal Ripken were the postmaster general. It is, however, a more intrepid foe to meteorological mishaps than most other civilian services.

The post office’s seemingly undeterred reliability brings to mind the familiar epigram, “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.”

Though some critics have suggested that a variation on the 1980s Orson Welles Paul Masson wine commercial, “We will deliver no mail before it’s time,” might be more appropriate and even though it’s not the official post office motto, the recent historic weather conditions have triggered deeper interest in it. That’s especially true here in Maine since the first adversary to which the slogan refers, “snow,” is an item we have recently produced in abundance.

The well known saying made its first and most prominent American appearance in 1914. That’s when it was placed above the entrance to the Farley Post Office opposite Penn Station in New York City, the brainchild of Boston born architect William Mitchell Kendall.

Kendall credited the expression to a 2,500-year-old account by the Greek historian Herodotus for the courier service of the Persian Empire.

To be sure, private communications and delivery systems that compete with the modern day American post office can also lay claim to such efficiency. However, as the primary government sponsor of such services it is still the lodestar in this arena.

Besides the Penn Station Post Office Kendall is also known as an architect for the Washington Square Arch that forms the terminus of Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue.

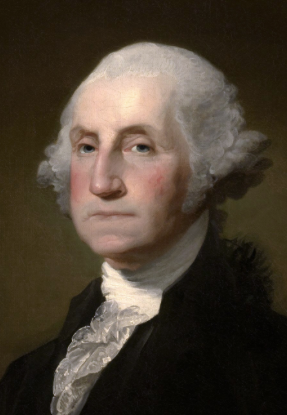

His association with a memorial to our first president and the imminence of another Presidents’ Day occasions an interest in how the holiday came about. (It’s also the type of event that might have even suspended deliveries in ancient Persia.)

In the first place, it’s of course well known that Washington wasn’t born on the third Monday of February. Indeed, under the calendar system in use at the time of his birth it was Feb. 11, 1731. A switch in 1752 in America to our present so-called Gregorian calendar shifted the birth date to Feb. 22, 1732. The change was due in part to the fact that not only were 11 days dropped from the calendar but that New Year’s Day was moved up from March 25 to Jan. 1.

In retroactively transporting his birth to a later year, bestowing him a more youthful statistical identity, Washington would be part of a unique generation that would be the envy of many. The president whose fabled honesty about cutting down the cherry tree did not need to lie about his age either. Confusion over the calendar came close to doing that for him.

In any event, it wasn’t until 1858, nearly 60 years after Washington’s death, that Maine began to open the door to some official recognition of his birth. This was a law that made the Feb. 22 date one of five which would re-set the grace period when promissory notes and other financial instruments like bank checks could be presented for payment.

Meanwhile, in 1885, Congress made Feb. 22 a day when federal offices were required to be closed.

It was not until 1929 that Maine followed suit and effective in 1930 made Feb. 22 a legal holiday for the state. There was no legislative debate over the change. Instead, lawmakers that session were in tight contention over whether to give an affiliate of Central Maine Power eminent domain authority so it could take over and flood such places as the town of Dead River and create what became Flagstaff Lake in the process. The bill was enacted only after a tie breaker vote cast by House Speaker Robert Hale.

It would be only a decade after the 1929 law when controversy over when to observe Washington’s birthday would be aroused.

This was when the movement to convert Washington’s birthday and four other holidays to a Monday first picked up steam in 1939. In that year, the Maine House became one of the first legislative bodies in the country to pass such a measure. Portland advertising executive, 27-year-old Joy Dow, in sponsoring the change heralded it as one that would benefit not only workers but also tourism, observing that “We spend, here in Maine, a fortune to develop the state as a recreation land for other people in other states…let us give the people of Maine five weekends when they too can enjoy the finest State in the forty-eight.”

Dow’s bill was defeated in the Senate, however, when older legislators including sons of Civil War heroes stressed the perceived sanctity of observing the holidays involved, especially Memorial and Veterans days, on their “real” date.

Dow’s idea was picked up in the mid-1950s by Bath legislator Rodney Ross and it finally won enactment in 1969. Impetus for the change was the Uniform Monday Holiday Act passed at the federal level in 1968 to be effective in 1971. Also influencing the decision was the Monday holiday orientation of British Commonwealth countries including Canada.

Maine’s law got the jump on the national one by moving up the state’s own observance to those occurring after Oct. 1, 1969.

The law making most legal holidays to fall on a Monday has since been tweaked by moving Veterans Day back to its original Nov. 11 date effective in 1978. We also followed the federal law that added Martin Luther King Day in the mid-1980s but since 1970, Washington’s Birthday sometimes also known as “Presidents’ Day” has been a Monday in Maine.

The day of course is not the “real” birthday of any president and is also informally designed to honor Abraham Lincoln’s of Feb. 12. The X and Millennial generations that have come of age since the advent of a predominantly Monday holiday culture might also consider the practice of the last several decades to have acquired an authenticity of its own.

Time will tell. Maybe an email holiday is on the horizon.

Paul Mills is a Farmington attorney well known for his analyses and historical understanding of public

affairs in Maine. He can be reached at pmills@myfairpoint.net.

Always fascinating to hear from Paul, the historian extraordinaire. Thanks for this tidbit that I will remember and share!

Congratulations Susy on your own birthday shared with George this year!

Seems like when I was a kid (early 70’s) we had Lincoln’s birthday and Washington’s birthday as holidays. Didn’t they merge the holidays together to create President’s Day?

Back in the olden days when I went to school, both Feb. 12 , Lincoln’s birthday, and Feb 22 , Washington’s birthday, were school holidays.

As between Lincoln’s and Washington’s, Washington’s was the only legal holiday even though there were widespread observances for both. When Maine, influenced by the federal change, shifted to the Monday holiday system in the late 60’s it technically retained by statute the reference to Washington’s Birthday even though a) It’s typically referred to as Presidents’ day and as such to take cognizance of Lincoln’s as well and b) It can never fall on Washington’s actual birthday since the 22nd would never be a third Monday!

And, Mark Ancker, we celebrated Memorial Day on May 30th, not on a Monday.

Thanks Paul, for these historic facts. Love great trivia!

Thank you, Daily Bulldog, for publishing the articles by Paul Mills. I always learn so much. Keep them coming