By Paul Mills

Standard time is back with us again. With it comes an extra hour in which to consider what is being decided Tuesday. Highlighting public interest in Maine are elections for mayor in the state’s two largest cities, Portland and Lewiston. Local elections and referenda issues in a few other places are also showcased on municipal marquees.

On the ballot everywhere in the state is a $105-million transportation bond issue. Bond issues are a perennial event and since the mid-1990’s 73 out of the 76 proposed by the legislature including all transportation borrowings have won voter approval. It’s almost a foregone conclusion that the same will hold true Tuesday.

There’s also a proposed constitutional amendment. Voting on them is more unusual. Though in the last eight years 29-bonds have gone out to voters, only twice in the same time period has there been an opportunity to weigh in on constitutional questions. Such voting also has a more unpredictable prognosis. Ten of the last 33 have gone down to defeat.

The proposed amendment we’re voting on this week would allow the legislature to pass a law to make it easier for persons who are physically unable to sign a citizen initiative or people’s veto petition. Though Maine law already permits such persons to allow another voter at his or her directive to sign all other election related forms including voter registration cards and candidate nominating petitions, the constitution as now written prohibits such assistance when it comes to initiative and people’s veto petitions. The proposed amendment would lift this restriction. If it passes the legislature could specify alternative means for persons whose hands, for example, are so crippled with arthritis that they cannot personally sign an initiative petition. If it passes, a law could be enacted that allowed such persons to use a signature stamp or to let someone else sign for them.

This election is a special landmark for a constitutional question. For the vote Tuesday comes just a few days after the 200th anniversary of the convention that gave birth to the original document that Tuesday’s vote seeks to amend. A quick look back to commemorate the occasion is thus in order.

Though Congress did not officially admit Maine as the 23rd state until March 1820, it needed to know ahead of time how its government would be organized. The procedure required that its people adopt a constitution which could then be evaluated by Washington lawmakers as they considered whether to give us statehood. Part of the scrutiny in Maine’s case was whether letting us in would tip the balance in favor of “free” states over “slave” states. The issue was ultimately resolved by the Missouri compromise, which provided that the free and slave states would be equally represented, Maine being a state that outlawed slavery and Missouri being one whose constitution allowed it.

Though the proposed new Maine government followed Massachusetts’ lead in outlawing slavery – something it had done in 1783 – the constitution that emerged from the October 1819 convention included a host of features that set the state apart from Massachusetts not only physically but philosophically. These reflected the views of the emerging Democratic-Republican or Jeffersonian ideology over those of the more conservative Federalists. (Among the latter, however, were still to be counted a number of prominent civic and political leaders including Stephen Longfellow, father of the future author of Paul Revere‘s Ride, who like most Federalists were opposed to separating from Massachusetts.)

The Declaration of Rights clauses of the Maine constitution, for example, guaranteed freedom of speech, a provision that Massachusetts had not embraced. Likewise, the draft of our constitution that came out of the 1819 convention also did away with religious favoritism. Maine not only did away with any established religion – which in the Bay State meant supporting Congregationalists at the expense of other denominations – but also guaranteed religious freedom.

Voting rights in Maine were also more expansive. While the Massachusetts regime had required that voters must have assets of at least sixty pounds or have an annual income of at least three, framers of the new Maine government did away with such restrictions. (It would of course be another century before women were also given the franchise by either government.)

A similar egalitarian shift away from Massachusetts occurred in the way Maine’s senate districts were apportioned. The Bay State awarded representation based on wealth while in Maine the districts were based primarily on population.

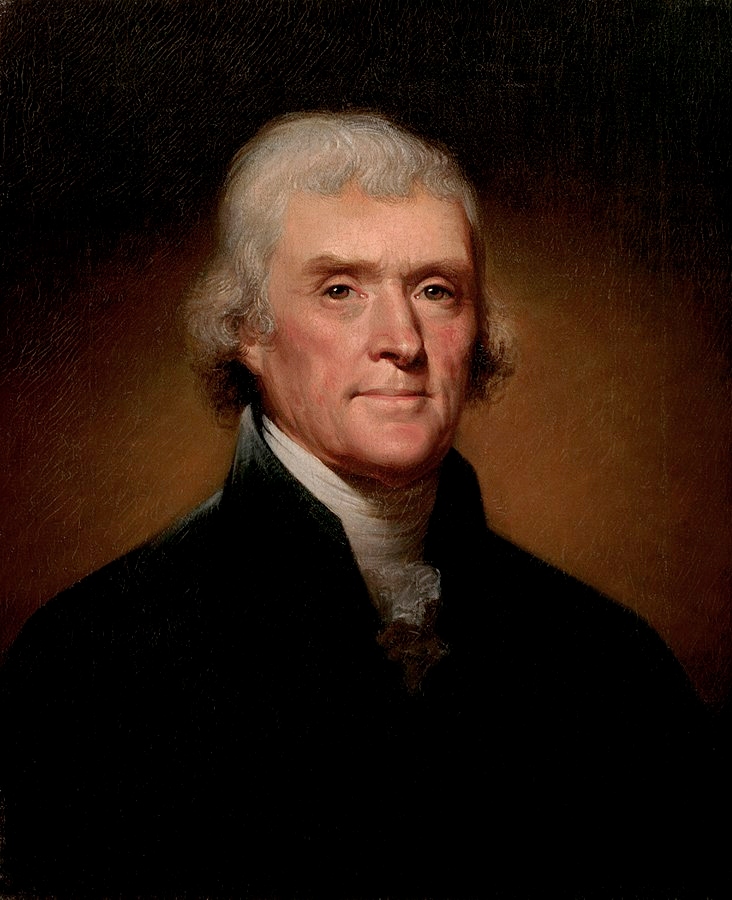

The democratic ideals of Thomas Jefferson were clearing winning out over the more authoritarian themes of such Federalists as Alexander Hamilton and Stephen Longfellow.

Though Jefferson did not personally attend the Convention he provided personal input to the Convention’s president, William King, soon to be the state’s first governor. In this the sage of Monticello – who in the same year was establishing the University of Virginia – is credited with providing the substance of provisions that were another departure from the Massachusetts constitution. This was the article that mandated local communities to financially support public education, the Massachusetts constitution merely encouraging such expenditures.

Jefferson was by no means completely pleased, however, with the all provisions that King’s convention would adopt. In a letter to King just after its adjournment he lamented that apportionment of the house of representatives was not completely according to population. Jefferson objected to the provision that the 1819 convention imposed which put a cap on the number of representatives to which larger communities would be entitled. His prediction to King, however, that such a clause would be amended proved prophetic, even though it would not be until 1963 that this would occur.

Even though Tuesday’s proposed amendment is unlikely to be one that either Jefferson or William King would have specifically anticipated its provisions making it easier for disabled voters to sign initiative and veto petitions would likely be in keeping with Jeffersonian influences.

Paul Mills is a Farmington attorney well known for his analyses and historical understanding of public affairs in Maine; he can be reached by e-mail pmills@myfairpoint.net.

What a lot of great information about our statehood history, thanks Paul!

Thanks as always, Paul for a well-written, informative and timely piece about our history. Wish you’d been my history teacher!

I always learn something interesting when I read your column!! And reading this column makes me so proud of my Maine connections. Thank you, Paul.

I love how you connect current issues with the values of the founders. Quite often in the modern “issue of the moment” we lose sight of the fact this is an almost 250 year old system with core values that have proven powerful and resilient! It is important to look at today with an understanding of yesterday.

Thanks for some interesting information to add to the memory banks. I enjoy Maine history a great deal. Never know when these bits of information will join with others and expand into greater knowledge, or if they may cross paths with someone’s genealogy and add details for their past. Another interest of mine.

Interesting to see how Maine’s Constitution so clearly reflect the move from restricted suffrage based on income to a general suffrage. However, in most states, the arrival of general suffrage – meaning voting rights for men regardless of property – meant the end of voting rights for people of color, in particular free Black men. Wondering if that is another difference to the Bay State’s constitution or if Maine, being one of the first states to move to general suffrage, at first also extends that to people of color?